It is Saturday evening, November 22, 2025. I am catching up on my reading, studying the events of the world, particularly those that touch upon the core of my business, my lifestyle, and my interests. The article in The Wall Street Journal, "My Wife and I Planned Our Retirement Perfectly. Then She Got Sick," by Glenn Ruffenach, caught my eye.

I was unable to read it straight through. I got no further than the first few paragraphs before I had to put the paper down, stand up, and walk away. The reason was not hunger for food, but a deep, professional anger. There was simply no need for a man of the author's clear intelligence and capability to be struggling as he obviously is.

I want to be perfectly clear, I have incredible compassion for him and his wife. I do not know them personally, only through his written words, but their situation is heartbreaking. However, my profession demands that I see reality without sugarcoating, and the bottom line is this, many people who follow the "Do-It-Yourself" path never truly think through the whole, complex picture of aging.

Surprisingly, I have seen a positive shift in recent years. Younger retirees, my clients, have done an amazing job of acquiring long-term care insurance, saving money, and focusing not always on "growth, growth, growth," but on income planning, budgeting of assets, proper timing of those assets, and a holistic approach to their entire life plan. They are realizing that Assets Under Management, or AUM, is often a slow bleed commission, and ignoring the signs of aging, both physical and financial, is extremely dangerous.

I had to take several passes at this article before I could finish the whole thing. I was angry because I was disappointed. At the same time, I am profoundly glad he wrote it. When I was done, being a traditionalist, I pulled out a legal pad and a pen and began making my notes.

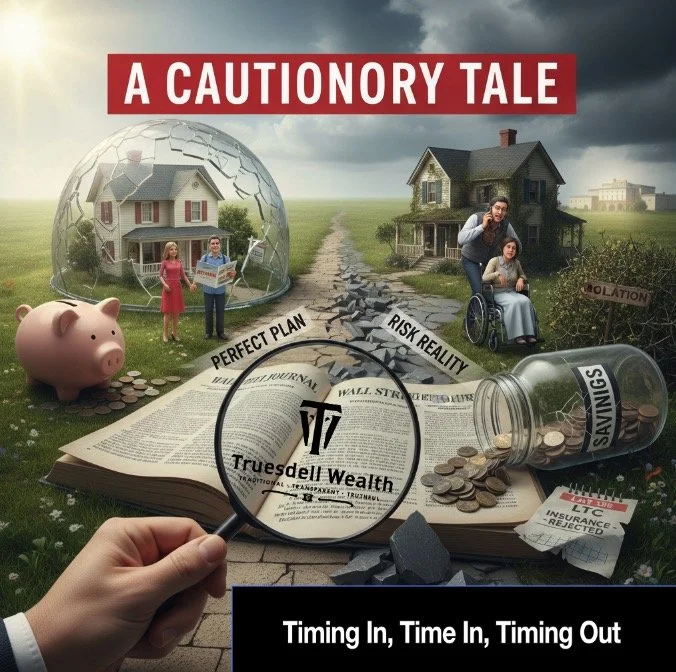

This analysis is written not to be nasty or mean, but as a cautionary tale. Mr. Ruffenach’s willingness to come forward is an honor, and his story is a generous, if painful, gift. I sincerely hope this review will help at least one or more people have that "aha" moment and adjust their own plans appropriately. There is so much to learn here.

DISCUSSION OF THE ARTICLE'S CONTEXT

The author, Glenn Ruffenach, explicitly states the irony of his situation, he spent decades writing about retirement planning, yet his own plan "ground to a halt" just four years after retiring due to his wife Karen's Alzheimer's diagnosis. The central issue is the failure to adequately plan for the high-impact, low-probability risks associated with aging and chronic illness, despite his professional expertise. His "perfect" plan was built on the fatal assumption of guaranteed continued health.

COMMENTARY ON FAILURE 1: HOUSING RISK MANAGEMENT, THE "AGING-IN-PLACE" CANARD

The author's inaction on their housing situation is a classic example of how procrastination creates non-financial burdens that accelerate burnout and stress.

The author admitted, "In hindsight, for instance, Karen and I should have downsized," having discussed it "for years." He stated that "inertia got in the way," leaving them in a "large empty nest (with our bedroom on the second floor)."

The author's regret is a profound understatement of the risk they undertook. "Aging in place" in an unsuitable, high-maintenance home is often a dangerous philosophy. The large, detached house actively isolates a couple, compounding risks like depression and loneliness, which are killers in retirement. Furthermore, the decision to stay put creates a hidden maintenance tax. What took a younger person a short time becomes an hours-long, exhausting endeavor for an older adult. This endless cycle of maintenance consumes energy and time, converting retirement into a never-ending job.

The author failed to recognize that downsizing the living space does not mean downsizing living itself. A proactive move to a smaller, single-story home or an independent living community is a strategic asset reallocation that buys back time, energy, and social capital. It provides a built-in safety net of compassionate neighbors, which is a crucial part of the non-financial long-term care support system. The author's current exhaustion from caregiving and home maintenance is the direct penalty for his and his wife's inertia.

COMMENTARY ON FAILURE 2: LONG-TERM CARE FINANCIAL RISK

The author’s failure to secure LTC coverage is the most critical financial misstep, directly impacting the longevity of their nest egg. The author confirms that "any bills tied to Karen's care will come entirely from our savings," with costs starting at "about $12,000 a month."

The deeper failure here is the absence of a comprehensive LTC System Plan. The author’s focus is narrow, almost exclusively on the expense and the failed insurance policy. This completely misses the holistic reality of long-term care.

A robust plan requires three pillars of mitigation. First, while insurance failed, the author did not mention proactive income planning vehicles, such as Charitable Remainder Trusts or income annuities, which are designed to shield assets and create guaranteed income for care. Relying solely on a savings account against catastrophic risk is unacceptable. Second, the author reports that fatigue is his "biggest problem" and that he is always tired, feeling the task is his "responsibility and mine alone." This dangerous isolation proves the failure to build a critical support network. Third, the failure to move into an optimal environment, like an active community, severely compounded the risk, accelerating caregiver burnout.

This article serves as a powerful illustration that successful personal finance requires a direct, comprehensive approach to aging risks that extends far beyond the simple purchase of insurance.

COMMENTARY ON FAILURE 3: EARLY DIAGNOSIS AND DENIAL

The author's greatest regret is his conviction that his wife's dementia began "much earlier" than they realized and that he was either in denial or missed some of the signs. He advises others to seek help "sooner rather than later."

From an advisory perspective, this highlights a critical area where financial professionals must step beyond traditional investment advice. Family members, like the author, often succumb to denial, but this is dangerous because it closes the window for critical planning. The delay in diagnosis directly prevented them from applying for Long-Term Care insurance in time. Furthermore, it delayed access to potential medical treatments and prevented timely asset adjustments, such as downsizing, before the caregiving task became overwhelming.

The advisor must be the voice of objective risk management, gently but firmly introducing difficult topics like declining health and financial preparation for incapacitation. The author's admission of denial is a powerful caution, the greatest risk to a retirement plan is often the risk a client doesn't want to talk about.

AN INDEPENDENT FIDUCIARY REVIEW, CONCLUSION

My heart goes out to Mr. Ruffenach and his wife, Karen. His commitment is an act of deep and unquestionable love.

However, my professional duty as a fiduciary compels me to state the painful truth, the author failed his wife, his family, and himself. This article, written by a person who spent decades writing columns about retirement planning, is a textbook example of confusing journalistic knowledge with robust, real-world, risk-managed execution. The plan failed because it lacked the foundational risk management strategies that a true fiduciary advisor would mandate.

The author’s plan collapsed because it lacked three things, a robust LTC financial shield, a structured social support network, and an optimal housing environment.

This entire situation is what happens when complex, specialized risk management is left to the "Do-It-Yourself" approach. The author, who never mentions consulting an investment advisor, was functionally unprepared because he lacked the objective, comprehensive risk-management guidance that a true fiduciary provides.

The author’s plan failed because he planned for a perfect scenario instead of implementing protections against the inevitable risks of longevity and illness. His journey, though painful, confirms that the only successful plan is one that aggressively anticipates and hedges against the worst-case realities of aging.

Paul Grant Truesdell, JD, AIF, CLU, ChFC, RFC

Founder of the Truesdell Companies