The Revolving Door of AI Investing

The Revolving Door of AI Investing

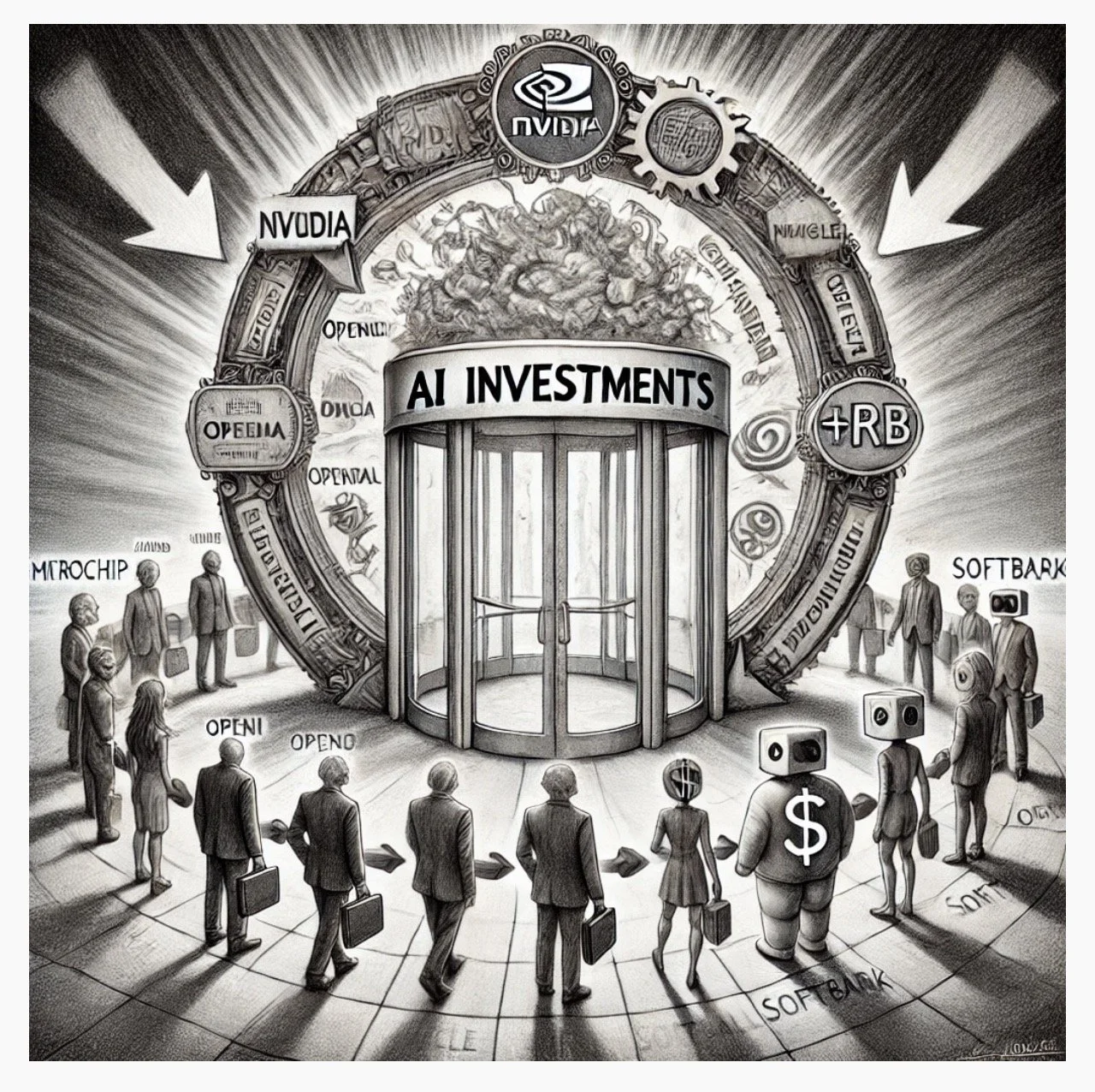

Right now, we’re watching a financial feedback loop form in the artificial intelligence sector — the same kind of circular logic that created the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s.

Example 1: Nvidia and OpenAI Nvidia is investing roughly $100 billion into OpenAI. At the same time, OpenAI spends a large portion of its capital buying Nvidia’s chips and cloud systems. In simple terms, Nvidia is paying OpenAI, which then pays Nvidia back — inflating both companies’ perceived value without introducing much new capital from outside. On paper, Nvidia’s $100 billion investment could appear to generate $500 billion in value, but much of that number is self-referential. It’s like loaning money to yourself and then calling it income.

Example 2: Meta, Oracle, and Cloud Computing Meta (Facebook’s parent company) is exploring a $20 billion AI cloud deal with Oracle. Oracle’s entire business model is based on filling data centers with expensive servers. So when Meta pays Oracle, Oracle uses that revenue to buy more hardware from the same companies that Meta and OpenAI rely on — primarily Nvidia. Again, we have money circulating in a small, closed loop of tech giants that all buy from and invest in each other.

Example 3: Broader Market Speculation At the same time, TikTok U.S. is valued at around $14 billion, comparable to Snapchat or Pinterest — companies that also rely heavily on AI and advertising algorithms. Meanwhile, Apple and Amazon are both repositioning: Apple is developing new internal Siri tools, and Amazon is shifting its grocery model into a digital marketplace. Netflix is even entering live sports, buying expensive streaming rights for MLB games — chasing the next “AI-enhanced” growth story.

Example 4: AMD and OpenAI AMD has entered a multi-year deal to supply chips to OpenAI, and in parallel OpenAI may obtain up to a 10 percent stake in AMD through purchase warrants. In essence, OpenAI becomes both a major customer and a potential owner of its hardware supplier — mirroring the circular dependencies forming across the AI supply chain.

Example 5: Nvidia and Reflection AI Nvidia led a multibillion-dollar funding round for Reflection AI, a startup building large-scale model infrastructure that will in turn rely heavily on Nvidia’s chips and software. The investment boosts Reflection AI’s valuation while guaranteeing future hardware demand for Nvidia — the same money looping back through its own ecosystem.

Example 6: Nvidia and xAI (Elon Musk) Elon Musk’s xAI is raising tens of billions in capital, including funding directly tied to Nvidia. Musk’s new AI venture will buy Nvidia chips at scale, meaning Nvidia profits both as supplier and investor. It’s a replay of the same self-reinforcing structure seen in the OpenAI cycle.

Example 7: CoreWeave and OpenAI / Nvidia CoreWeave, one of Nvidia’s fastest-growing partners, signed an $11.9 billion infrastructure contract with OpenAI and is preparing for an IPO that could give OpenAI an ownership stake. CoreWeave’s entire business model is built on deploying Nvidia hardware — another instance of intertwined financing and consumption that inflates valuations on both sides.

Example 8: Stargate (Joint Venture of OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank) A new joint venture called Stargate aims to build next-generation AI data centers. The same three companies — OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank — are simultaneously the investors, customers, and infrastructure providers. Each profits from the other’s spending while reinforcing the same circular structure.

Example 9: SoftBank and Ampere Computing SoftBank recently acquired Ampere Computing, a chip manufacturer, while continuing to invest heavily in AI startups and infrastructure ventures. That makes SoftBank both supplier and financier in multiple layers of the same AI hardware economy — magnifying concentration risk if demand cools.

Example 10: Nvidia, Oracle, and Mutual Investee Flows Analysts now note a broader triangle among Nvidia, Oracle, and their portfolio companies: Nvidia sells chips to Oracle, Oracle leases compute power to Nvidia-backed startups, and those startups in turn attract fresh investment from both Nvidia and Oracle. Each transaction reinforces valuations in the others — a classic hallmark of speculative interdependence.

Why It’s Dangerous for Regular Investors

To the average investor — those with 401(k)s, IRAs, and mutual funds — this circular activity looks like innovation and expansion. But under the surface, it’s a speculative echo chamber. Companies are valuing themselves based on money they spend within the same small group of firms. It’s not true productivity; it’s accounting smoke and mirrors.

This mirrors the dot-com era, when internet companies bought advertising from each other to boost revenue, only to collapse when real profits failed to appear. When the cycle breaks — when spending slows or regulation tightens — valuations can drop by 50 to 80 percent overnight. And because so many retirement portfolios are now overweight in tech and AI funds, a major correction could ripple through the entire market.

The Bottom Line

When money circulates within a closed system — Nvidia funding OpenAI, OpenAI buying Nvidia hardware, Meta leasing Oracle servers, Oracle buying Nvidia chips — everyone looks rich until the music stops. The moment new cash from outside investors slows down, the illusion of perpetual growth evaporates.

It’s not that AI is fake; it’s that the valuation mechanics have become self-referential. And history shows that when hype exceeds real-world output, rank-and-file investors pay the price while insiders cash out early.

Expanded Version

The Revolving Door of AI Investing — An Expanded Cautionary Study

Right now, we’re watching a financial feedback loop form in the artificial intelligence sector — the same kind of circular logic that created the dot-com bubble of the late 1990s.

Example 1: Nvidia and OpenAI

Nvidia is investing roughly $100 billion into OpenAI. At the same time, OpenAI spends a large portion of its capital buying Nvidia’s chips and cloud systems. In simple terms, Nvidia is paying OpenAI, which then pays Nvidia back — inflating both companies’ perceived value without introducing much new capital from outside. On paper, Nvidia’s $100 billion investment could appear to generate $500 billion in value, but much of that number is self-referential. It’s like loaning money to yourself and then calling it income.

Example 2: Meta, Oracle, and Cloud Computing

Meta (Facebook’s parent company) is exploring a $20 billion AI cloud deal with Oracle. Oracle’s entire business model is based on filling data centers with expensive servers. So when Meta pays Oracle, Oracle uses that revenue to buy more hardware from the same companies that Meta and OpenAI rely on — primarily Nvidia. Again, we have money circulating in a small, closed loop of tech giants that all buy from and invest in each other.

Example 3: Broader Market Speculation

At the same time, TikTok U.S. is valued at around $14 billion, comparable to Snapchat or Pinterest — companies that also rely heavily on AI and advertising algorithms. Meanwhile, Apple and Amazon are both repositioning: Apple is developing new internal Siri tools, and Amazon is shifting its grocery model into a digital marketplace. Netflix is even entering live sports, buying expensive streaming rights for MLB games — chasing the next “AI-enhanced” growth story.

Additional Examples of Circular / Interdependent AI Investing

Example 4: AMD and OpenAI AMD has entered a multi-year deal to supply chips to OpenAI, and in parallel OpenAI may obtain up to a 10 percent stake in AMD through purchase warrants. In essence, OpenAI becomes both a major customer and a potential owner of its hardware supplier — mirroring the circular dependencies forming across the AI supply chain.

Example 5: Nvidia and Reflection AI Nvidia led a multibillion-dollar funding round for Reflection AI, a startup building large-scale model infrastructure that will in turn rely heavily on Nvidia’s chips and software. The investment boosts Reflection AI’s valuation while guaranteeing future hardware demand for Nvidia — the same money looping back through its own ecosystem.

Example 6: Nvidia and xAI (Elon Musk) Elon Musk’s xAI is raising tens of billions in capital, including funding directly tied to Nvidia. Musk’s new AI venture will buy Nvidia chips at scale, meaning Nvidia profits both as supplier and investor. It’s a replay of the same self-reinforcing structure seen in the OpenAI cycle.

Example 7: CoreWeave and OpenAI / Nvidia CoreWeave, one of Nvidia’s fastest-growing partners, signed an $11.9 billion infrastructure contract with OpenAI and is preparing for an IPO that could give OpenAI an ownership stake. CoreWeave’s entire business model is built on deploying Nvidia hardware — another instance of intertwined financing and consumption that inflates valuations on both sides.

Example 8: Stargate (Joint Venture of OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank) A new joint venture called Stargate aims to build next-generation AI data centers. The same three companies — OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank — are simultaneously the investors, customers, and infrastructure providers. Each profits from the other’s spending while reinforcing the same circular structure.

Example 9: SoftBank and Ampere Computing SoftBank recently acquired Ampere Computing, a chip manufacturer, while continuing to invest heavily in AI startups and infrastructure ventures. That makes SoftBank both supplier and financier in multiple layers of the same AI hardware economy — magnifying concentration risk if demand cools.

Example 10: Nvidia, Oracle, and Mutual Investee Flows Analysts now note a broader triangle among Nvidia, Oracle, and their portfolio companies: Nvidia sells chips to Oracle, Oracle leases compute power to Nvidia-backed startups, and those startups in turn attract fresh investment from both Nvidia and Oracle. Each transaction reinforces valuations in the others — a classic hallmark of speculative interdependence.

Historical Parallels and Lessons

To understand why this pattern is worrying, we have to look back at prior bubbles and failures. The story of speculative excess is as old as capitalism itself. From tulip bulbs to technology stocks, the underlying human behaviors — greed, momentum, and belief in perpetual motion — remain unchanged.

Tulip Mania (1634–1637)

The Dutch tulip bubble remains one of the earliest recorded speculative manias. Between 1634 and 1637, prices of certain tulip bulbs — especially rare hybrids like the Semper Augustus — rose to absurd levels. Contracts for future delivery were traded at prices exceeding the cost of a home. Ordinary merchants, farmers, and artisans speculated on bulbs they never intended to plant.

When confidence faltered in early 1637, the market collapsed overnight. The “tulip fever” destroyed fortunes, strained the Dutch economy, and provided a permanent metaphor for irrational speculation. Tulip Mania’s lesson is timeless: when assets trade far beyond intrinsic value, the collapse is always sudden, merciless, and complete. The AI investment frenzy today, built on recursive corporate valuation and exaggerated demand for computational power, echoes this same psychological cycle of mass belief in infinite growth.

Florida Land Mania and Charles Ponzi’s Second Act (1920–1926)

Before the Great Depression, America experienced another extraordinary speculative craze — the Florida Land Boom of the 1920s. Encouraged by cheap credit, rapid population growth, and the promise of endless sunshine, investors across the nation poured money into Florida real estate sight unseen. Railroads, glossy brochures, and glowing newspaper ads promoted visions of paradise and profit. In truth, much of what was being sold was swampland — undevelopable, inaccessible, and often underwater.

Among the most notorious figures of the era was Charles Ponzi, whose name had already become synonymous with financial deceit. After his original postal coupon scheme collapsed, Ponzi migrated to Florida, establishing the Charpon Land Syndicate. He began selling plots of “prime development property” near Jacksonville, promising investors that their holdings would double or triple in value within 90 days. The reality was far more sinister: the land was useless marshland, unfit for building or farming. Ponzi’s sales pitch was a repackaged version of his earlier fraud — using investor optimism to fund artificial “profits” and maintain the illusion of success.

As the Florida real estate boom reached its peak in 1925, prices climbed 500 percent in some areas. Newcomers lined up to buy lots that often hadn’t even been surveyed. When hurricanes, transportation bottlenecks, and bank failures converged in 1926, the entire system imploded. Thousands lost their savings. Ponzi was arrested again and ultimately deported, cementing his place in financial history not just as a swindler but as a symbol of how confidence schemes thrive in speculative climates.

This Florida saga mirrors the AI cycle in key ways: inflated valuations, circular promotion, hype-driven demand, and faith in perpetual expansion. Like investors in Florida’s “new frontier,” today’s AI enthusiasts are betting on abstractions — promises of returns that rely on endless optimism and constant inflows of fresh capital.

The Great Depression & 1929 Stock Market Collapse

The 1920s stock boom followed the same dangerous rhythm of unchecked optimism. The U.S. economy appeared invincible, fueled by industrial expansion, credit leverage, and unregulated speculation. Retail investors bought stocks on margin, borrowing 90 percent of the purchase price. Prices rose because everyone believed they would keep rising.

In October 1929, the illusion broke. The market crashed, wiping out nearly 90 percent of equity value over the next three years. The collapse triggered the Great Depression — a decade of mass unemployment, deflation, and institutional failure. The crash revealed the fragility of systems built on circular leverage and faith instead of tangible productivity.

Just as investors in the 1920s borrowed to buy paper wealth, today’s AI valuations depend on an endless chain of reinvestment, cross-ownership, and speculative narratives detached from real output. The warning is clear: when confidence is collateral, collapse is inevitable.

The Dot-com Bubble (1995–2000)

- During the late 1990s, many internet companies that lacked real earnings inflated their valuations through cross-advertising, intercompany deals, and speculative capital flows. Many bought ad space from each other to boost revenue metrics.

- When the bubble burst in 2000, a large fraction of those companies collapsed, erasing trillions in market value.

- The era produced a generation of retail investors who learned too late that market excitement is not a substitute for profitability.

- The concept of “irrational exuberance” became shorthand for the mania of believing that technological innovation alone guarantees permanent economic growth.

The 2000s U.S. Housing Bubble & Financial Crisis

- In the mid-2000s, easy credit, speculative home investments, and financial engineering (mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations) transformed housing into a speculative asset class distributed globally.

- The collapse in home prices triggered defaults that cascaded through the financial system, exposing how widespread leverage and derivative opacity could magnify systemic risk.

- Pension funds and municipalities — considered “safe money” — suffered catastrophic losses when supposedly secure mortgage assets turned out to be toxic.

- Once again, financial innovation detached from reality ended in ruin.

Ponzi Schemes and Bernie Madoff

The purest modern echo of circular valuation is the Ponzi scheme — a structure that relies entirely on new capital to sustain the illusion of returns. Bernie Madoff’s multibillion-dollar fraud was the most sophisticated of its kind. For decades, he reported stable, above-market gains to investors, attracting pension funds, charities, and wealthy families. In truth, Madoff generated no profits. He used new deposits to pay old clients, maintaining the appearance of success through falsified statements and a reputation for exclusivity.

When the 2008 financial crisis hit and redemption requests surged, the system collapsed in days. More than $60 billion in paper wealth vanished. The parallels to AI valuations are striking: consistent returns that appear risk-free, institutional validation, and opaque structures too complex for outside scrutiny.

Like Madoff’s victims, today’s investors may not recognize that their gains are being recycled within the system — the same money circulating among AI companies, chip makers, and cloud providers, creating the illusion of unstoppable progress.

Why This Feeds Directly into the Revolving Door Thesis

- The historical bubbles show that when capital becomes detached from real demand or productivity, the system becomes fragile. Circular financial loops amplify that detachment.

- Just as internet firms in the dot-com era inflated revenue via intercompany buys, today’s AI/infra firms are inflating demand via internal cross-flows and equity stakes.

- Once sentiment turns or funding dries up, the same circular structure can reverse violently: investments dry, customers default, partner companies lose value in lockstep.

- Because large institutional portfolios, pensions, and funds chase growth, they often concentrate exposure in tech/AI themes — making them highly vulnerable to synchronized corrections.

Threats to Rank-and-File Investors, Pensions & Funds

- Concentration Risk – Heavy weighting toward AI and tech magnifies systemic exposure.

- Valuation Risk & Illiquidity – When internal flows drive value, liquidity evaporates first in downturns.

- Fire Sales & Amplification – Forced selling by funds accelerates losses.

- Interconnected Failures – Supplier-customer loops create domino effects.

- Regulatory & Sentiment Shocks – Policy or perception changes can break feedback cycles overnight.

- Misallocation of Capital – Speculative hype diverts investment from sustainable enterprise.

- Erosion of Trust – Each collapse reduces public faith in markets, harming long-term capital formation.

Confirmation & Current Warnings

- Analysts across financial media have noted that Nvidia’s AI investments “artificially overstate” sector demand.

- The Guardian’s Nils Pratley called the AI valuation loop “silly and circular.”

- The Bank of England warns that tech equities are “particularly exposed” to a sharp correction if enthusiasm fades.

- Pension research groups like Equable flag valuation risk as an “emerging systemic threat” to public funds.

- Scholars writing on the “illusion of the perpetual money machine” warn that every generation convinces itself it has transcended the limits of real productivity — until it hasn’t.

Conclusion & Cautionary Imperatives

History does not repeat, but it rhymes with alarming precision. From tulip bulbs to swampland deeds, from mortgage tranches to AI tokens, the mechanism is always the same: belief outpaces reality, and valuation detaches from output.

For rank-and-file investors, pension holders, and fiduciaries, the warning is plain: Do not confuse innovation with immunity. Diversify. Demand transparency. Follow the money — and if it never leaves the same circle, step away.

When the revolving door of AI investing finally slows, it won’t be the executives who suffer. It will be the ordinary investors, the retirees, and the pensioners — those who trusted that history’s oldest lesson no longer applied.

Sources

Bank of England. Financial Policy Committee Statement on Equity Markets and Systemic Risk. London: Bank of England, October 8, 2025. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/boards-policy-regulation/bank-england-fpc-equity-markets-are-particularly-exposed-should-expectations-2025-10-08/.

Bernanke, Ben S. Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

CFA Institute. “Buyers Beware: 7 Red Flags That Signal a Private Market Reckoning.” CFA Institute Investor Blog, July 3, 2025. https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2025/07/03/buyers-beware-7-red-flags-that-signal-a-private-market-reckoning/.

Equable Institute. Emerging Threats to America’s Public Pensions: Valuation Risk and Market Volatility. New York: Equable Institute, 2025. https://equable.org/emerging-threats-to-americas-public-pensions/.

Galam, Serge. “The Invisible Hand and the Rational Agent Are Behind Bubbles and Crashes.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.02990, 2016. https://arxiv.org/abs/1601.02990.

Investopedia. “Why Wall Street Analysts Say We’re Not in an AI Bubble — Yet.” Investopedia, September 2025. https://www.investopedia.com/wall-street-analysts-ai-bubble-stock-market-11826943.

Jorion, Philippe. Financial Risk Manager Handbook. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2007.

Kindleberger, Charles P., and Robert Z. Aliber. Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises. 7th ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Krugman, Paul. The Return of Depression Economics and the Crisis of 2008. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2009.

Minsky, Hyman P. Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1986.

Minsky, Hyman P. “The Financial Instability Hypothesis.” Working Paper No. 74. Jerome Levy Economics Institute, May 1992.

Niederhoffer, Victor. “The Tulipmania: Fact or Artifact?” Journal of Political Economy 97, no. 3 (1989): 535–560.

Pratley, Nils. “The AI Valuation Bubble Is Now Getting Silly.” The Guardian, October 8, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/nils-pratley-on-finance/2025/oct/08/the-ai-valuation-bubble-is-now-getting-silly.

Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Sornette, Didier. “The Illusion of the Perpetual Money Machine.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1212.2833, 2012. https://arxiv.org/abs/1212.2833.

U.S. Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission. Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2011.

U.S. Department of Justice. “Justice Department Announces Distribution of Over $1.589 Billion to Nearly 25,000 Victims of Madoff Ponzi Scheme.” Press release, November 17, 2021. https://www.justice.gov/archives/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-distribution-over-1589m-nearly-25000-victims-madoff-ponzi.

Wikipedia. “2008 Financial Crisis.” Last modified August 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2008_financial_crisis.

Wikipedia. “Dot-com Bubble.” Last modified August 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dot-com_bubble.

Wikipedia. “Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission.” Last modified July 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Financial_Crisis_Inquiry_Commission.

Wikipedia. “Irrational Exuberance.” Last modified June 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irrational_exuberance.

Wikipedia. “Ponzi Scheme.” Last modified September 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ponzi_scheme.

Wikipedia. “Swampland in Florida.” Last modified May 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swampland_in_Florida.

Wikipedia. “Tulip Mania.” Last modified April 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tulip_mania.

Yale School of Management. “This Is How the AI Bubble Bursts.” Yale Insights, August 2025. https://insights.som.yale.edu/insights/this-is-how-the-ai-bubble-bursts.

Yahoo Finance. “The AI Boom’s Reliance on Circular Deals Is Raising Fears of Overheating.” Yahoo Finance, October 2025. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/ai-booms-reliance-circular-deals-223120705.html.