Kneel or Else

Kneel or Else

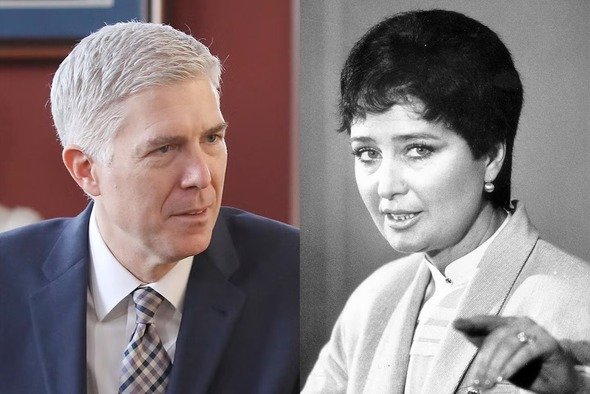

Neil Gorsuch, an Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, has had a distinguished legal career. However, a lesser-known part of his family history involves his mother, Anne Gorsuch Burford's legal battle with Congress during her tenure as Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under President Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s.

Anne Gorsuch Burford, a conservative Republican lawyer from Colorado, was appointed by Reagan to lead the EPA in 1981. As EPA Administrator, she sought to scale back environmental regulations and enforcement actions, in line with the Reagan administration's deregulatory agenda. This approach brought her into conflict with the Democratically-controlled House of Representatives.

In 1982, as part of its oversight responsibilities, a House subcommittee chaired by Representative Elliott Levitas (D-GA) subpoenaed EPA documents related to the agency's Superfund program and its enforcement of hazardous waste cleanup laws. When Burford refused to fully comply with the subpoena, citing executive privilege at the direction of President Reagan, the House voted in December 1982 to hold her in contempt of Congress. She became the highest-ranking executive branch official to ever face such a charge.

The contempt citation created a constitutional clash between the legislative and executive branches. The Reagan administration sued to block Burford's prosecution, seeking to transform the criminal contempt charge into a civil case. Meanwhile, the Justice Department declined to prosecute her. After months of legal and political wrangling, Burford resigned from the EPA in March 1983. She was never jailed or tried for contempt, although several lower-level EPA officials were convicted of lying to Congress during the investigations.

The Burford case highlights the highly political nature of contempt of Congress prosecutions. As the lists of individuals charged with contempt in recent years show, there is wide variation in how these cases are handled. Some officials, like Burford, face a contempt vote but avoid prosecution due to executive branch resistance or negotiated settlements. Others are convicted but receive little or no jail time. A rare few serve prison sentences.

The outcomes often depend on the political dynamics at play. When the White House and Congress are controlled by opposing parties, contempt charges become a tool for asserting institutional power and airing partisan grievances. For instance, the contempt charges against George W. Bush administration officials like Karl Rove and Harriet Miers went nowhere once President Bush asserted executive privilege. Similarly, President Barack Obama's Attorney General Eric Holder escaped prosecution after the House voted to hold him in contempt during the Fast and Furious gun-running scandal.

In contrast, when the same party controls both branches, contempt threats can be a means of forcing compliance from recalcitrant officials. This was evident in the recent prosecutions of former Trump advisors Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro by the Biden Justice Department after the Democrat-led House referred them for contempt charges related to the January 6 investigations.

The selective and politicized use of contempt charges raises troubling questions about the rule of law and the separation of powers. In theory, contempt of Congress laws exist to protect the legitimate oversight and investigative functions of the legislative branch. In practice, they are often wielded as political weapons, with the decision to prosecute heavily influenced by partisan considerations rather than the merits of the case.

This dynamic erodes public trust in government institutions and fuels perceptions that justice is not administered impartially. It suggests that legal accountability for public officials depends more on political power than on the evenhanded application of the law. This is a dangerous state of affairs in a constitutional democracy premised on equality under the law and constraints on the arbitrary exercise of authority.

To be sure, Congress's oversight powers are essential to maintaining the integrity of the executive branch and preventing abuses of power. There are times when administration officials should be held in contempt for defying legitimate subpoenas or engaging in misconduct. However, the process of charging and prosecuting contempt cases needs to be insulated from political influence as much as possible, with clear and consistent standards for when contempt referrals are justified.

Some have called for an independent counsel or special prosecutor who is automatically appointed to assess contempt charges whenever the House votes on such a resolution, rather than leaving it to the discretion of a presidentially-appointed Attorney General. The argument is that an independent counsel would depoliticize the decision to prosecute and ensure that the legal merits are evaluated objectively. This leads to the question of the right of Congress's oversight prerogatives, if any, and to what degree, when it comes to executive administration. Executive privilege and orders are such that those with a high degree of intentingal fortitude in the face of reckless congressional inquiries can run the nation akin to a four-year dictatorship, which is core to presidential functions in all corporate, charitable, educational, and governmental presidential positions. It is what it is, and facts are facts. In other words, when it hits the fan, the majority of the nation expects strong leadership, and the majority will fall in line.

Ultimately, the saga of Anne Gorsuch Burford's contempt battle with Congress and the broader problems it represents point to the fragility of America's constitutional system. When partisanship and the pursuit of political advantage override principles of checks and balances, transparency, and evenhanded justice, the foundations of democratic governance are weakened.

The U.S. certainly remains a far more robust and genuinely democratic polity than authoritarian-leaning states and developing countries where the politicization of justice is endemic. But the trends of recent administrations since the turn of the century have exemplified by contempt of Congress controversies, how pernicious political incentives, if left unchecked, can erode the rule of law and public faith in the constitutional order over time.

Resisting these dynamics will and has taken several forms. The need for impartial and professional ethos among federal officials is paramount, for as Cesar's crossing of the Rubicon, "there ain't no turning back."

Political courage is slim at best for many with much to lose and who have carried countless buckets for benefactors galore. The slippery slope may be ahead or behind, but to further descent into a political-based prosecutorial system where might make right, and where legal accountability becomes just another arena for tribalistic power struggles will likely result in a bad outcome